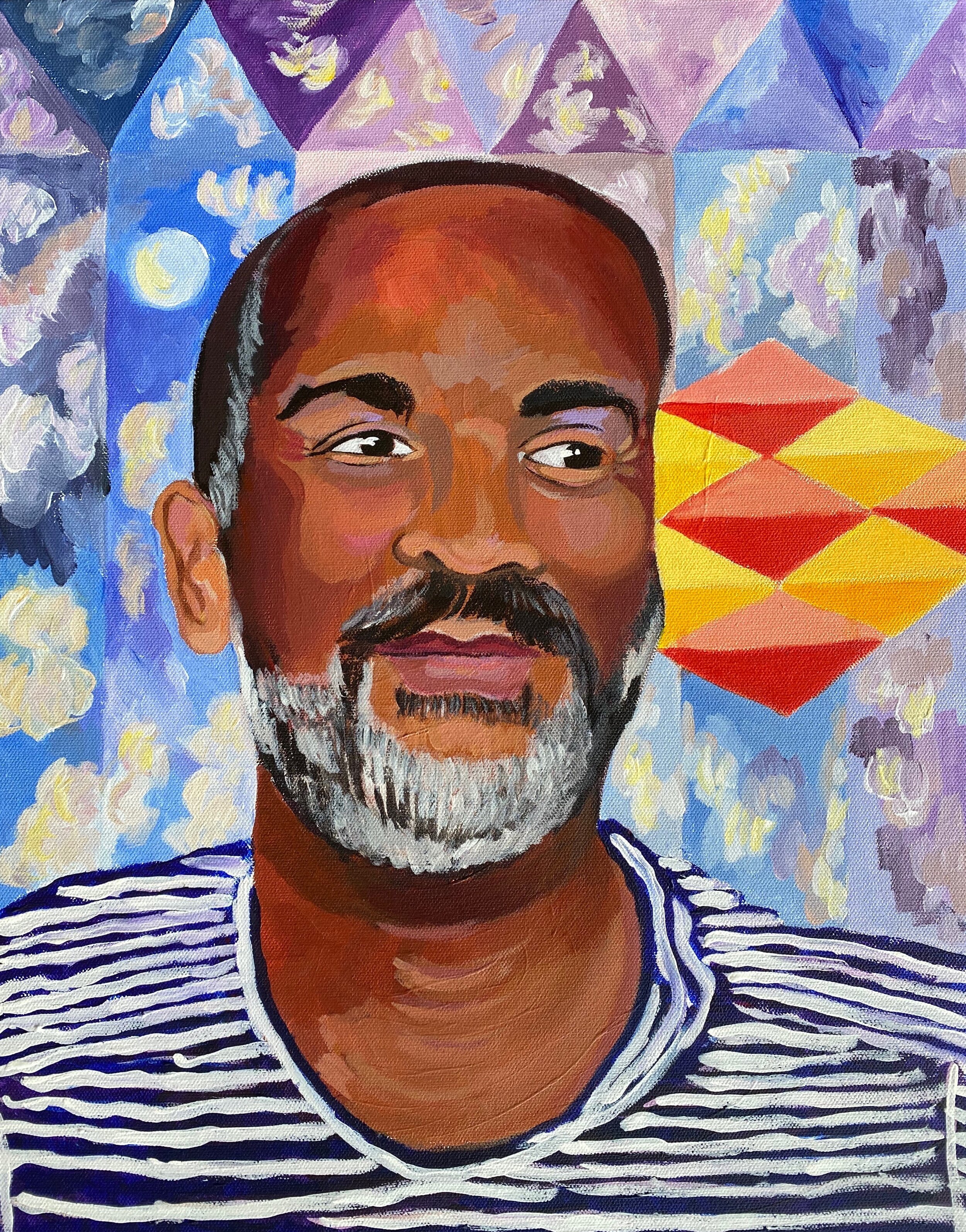

I’m so grateful for each and every conversation I share with my brilliant friend and confidant, Todd Palmer. Todd has worn a number of hats as a cultural worker (educator, arts administrator, curator) and creative (writer, installation artist), drawing from and sometimes reacting against his training in architectural design, history and theory. Todd and I share an upbringing in Denver - he grew up in a Black mixed class family in the 70s and I grew up in a white post-Soviet Jewish immigrant family in the 90s. Our conversation spans navigating our racial identities, speaking to ancestors, challenging institutions, and traveling across time and space to connect to our past and future selves.

Irina: Thank you so much for taking the time to thoroughly prepare for our conversation. I think you’re the only person to study every portrait, read every conversation that’s part of this series. I’m so honored and humbled! How did you get to be this way?

Todd: It’s how I was raised.

Irina: Tell me about it!

Todd: I’ve been thinking a lot about this in the context of this moment, of the country coming to terms with its anti-Blackness, with its racism. I was born in 1968, so just as a context -- my father, the year I was born, got a law degree. It was one of the first years that a Black man with a law degree was looking at a career in corporate America as opposed to serving the Black community. In retrospect, we can say, “Hm, was that a good thing or a bad thing?”

My grandfather, my mother’s dad, was a Black doctor working in Louisville, Kentucky for people in the Black community. That generational difference shaped who I am. My mom has always been the voice worried we were becoming oreos because we were growing up in this white world, and at the same time be prepared for any and everything.

I lived in Denver, went to public schools, was bussed to the “inner-city” as part of this integration project. But we were then already integrated into white neighborhoods, living on the verge of the suburbs. Summers were always programmed, so the fact that I do a lot of public programming, I’m like, “Hm, I was programmed to be a programmer.” Activities were key. We had our Black youth group that we’d go to and chorus, viola, piano, pottery, cooking class, swimming, tennis, I mean… and my mom was working so she’d sneak off of work to take us to the next class. We had an agenda -- we didn’t all take the same classes because she was personalizing our studies. I’ve been programmed in this way, and also, you see your mom doing too much and you’re like, “Well, that’s normal, right?”

I’m not working right now, and in looking for opportunities, it occurred to me: wait a minute… do people even know that I’m Black? From how I talk about myself professionally in my CV, I don’t quite say it… where does that come from?

I tend to say I’m the “behind the scenes person” and I think not claiming my identity upfront relates to this preference for not being in the picture. Being a neutral party… So I’ve been reflecting on how that happened… through this very specific time that I grew up in. The world has changed and I’m not so much catching up to it, but realigning myself to this moment has been probably what I’ve been doing in this time..

Irina: Yeah… so how do you think that happened? When you asked yourself, “How did I get to this place?”

Todd: I think part of it is… we were growing up in a racist society, and part of this “experiment” to integrate was from the premise that whiteness was something to assimilate into. If I did something, it was doubted. Let’s call affirmative action “basic level” reparation. For me, as a 17 year old, I went to Princeton. For my own self-worth and from this “preparation” mentality from my family, I said, well I’m going to do something at Princeton that only “I” can do. Separately from affirmative action. So that means, what? I must be the best in my class. I graduated with honors from architecture. Something on my CV that doesn’t matter -- ever or anymore -- but my grandparents felt really good about it. It was something that I could own, like, you can’t affirmative action your way into that.

Irina: Yes…

Todd: But that’s like, crazy-making… Now I’m like, what kind of pressure was I putting on myself to defy what shouldn’t have been in question in the first place.

Irina: And what could’ve been possible if you didn’t have that pressure…

Todd: Yeah.

Irina: So looking back, if you could meet your 17 year old self now, what would you say?

Todd: Hmm. So many things. I’ve been thinking that maybe I did go back, you know in this crazy way. That I made it through because even though I couldn’t see who I am now, deep down I knew that it would be okay… I remember moments, like literally I’d go out to the edge of the campus where there’s a forest… and just scream. Like, about everything -- love, my identity, my lack of friends, whatever -- and I don’t know. I feel like somehow that screaming was necessary… I let something out.

Irina: You know, it’s wild that you say that, I was just spending time with a friend who told me that they’re working with an ancestral healer and we were on the beach together and they was like, “You need to dig a hole in the ground and scream to it” like back to my ancestors. I wonder if you were screaming to your future self.

Todd: I’ve been mining my journals, postcards. I have a lot of correspondence from my maternal grandparents who traveled. They sent me a postcard from Sicily. And as I mine my own things, I found this photograph that I took in Spain… So, Sicily was in the ‘70s and I was in Spain in 2008. And it’s like the same photo: how bizarre. But it feels like a clue, like we’re leaving clues and signs for ourselves that we’ll make it through. Hopefully we’re paying attention.

So I would love to have been this person that didn’t put all this pressure on myself or this person, who 10 years ago was more stridently claiming their Blackness. But I wasn’t that person so I can’t really go back. What I do have now that I didn’t have then is that I have a stronger sense I’m on a path. And the path -- if I’m attentive -- takes me to places that I need to be. And I apply myself in the best ways I can to this journey. And somehow good comes out of that, or a lesson comes out of that, which is for the good, usually.

Irina: I like this idea of time travel connecting between yourself, your ancestors, your past and present -- Arundahti Roy said, “the pandemic is a portal” -- I think sometimes having that spaciousness allows us to see connections more clearly. Also, it sounds like you did what you needed to do to survive and you can’t be mad at yourself for that. You’re a product of your upbringing and your society and now you get to look back and make different choices, but it’s not better or worse.

Todd: I can say on one hand, I can’t go back and be a different kid. But I don’t need to downplay who I am, I don’t need to continue that. “We all have a certain amount of capacity to pivot and to become something different as we look at what’s ahead.”

Irina: What does your pivot look like right now?

Todd: For me, it’s still happening. I made the decision to step down from a position months before everything shut down, but the actual last day of work at the [Chicago Architecture] Biennial was March 31st and the lockdown started in the middle of March. I was planning to slow down and take stock of work that I’m proud of. But also, the context in which I was doing the work, institutionally, I did not have the power or energy to pivot that whole structure and I needed to step back. There were pressures of stepping into this existing Biennial, having to generate half a million tourists for the city, but also change the conversation about architecture... In the end it felt like fundamentally changing the conversation can’t be tied to connecting at some more basic level to tourists...there’s going to be a conflict.

Irina: Right, make us the most money AND tell the truth!

Todd: Right right! It’s still a work in progress… I think where I’m clear is that there’s a value to experimentation. We’re in this society that wants the answer always and fast. If you say, as you’re saying, “Abolish the police” -- the powers-that-be are like, “Well, we can’t because you haven’t translated that into this legal minutiae of everything that would have to happen to answer every question and every doubt. So we can’t, on a principle, do this big thing.” The protestors aren’t coming with the legal zoning code of what that means.

I was in a conversation to guide arts policy for the Lightfoot administration when she was the Mayor-elect. There were really great people in the room, like Amanda Williams for example... and I’m not going to name everyone. But there was a cross section of arts education, artists, myself, arts administration, and one of the things that came out was -- art can do so much more. And what is art?: defining it much more capaciously than art-making as something that is market-recognized in a frame. But art as activism, art as healing, art as community development, art as catalyst, as design, across the board. “We could approach many of the city’s problems by thinking artistically about them, creatively, organically, the possibility we teach problematically, the way we eat problematically, the way we structure our livelihoods in one place and commute to another place, whether on a transit or a car.”

We’ve created all these systems that the pandemic broke. While there’s never a tabula rasa, coming close to the possibility of saying, “Well, everything’s broken, how do we experiment in rejiggering these things together?” I think artists working with other architects and educators and public health officials, there could’ve been some really interesting re-envisioning. We’d have these thoughts where artists need to be everywhere, working with sanitation departments and schools. But not just the artist alone -- the artist as a networker to make sanitation talk to schools. There’s a transportation commissioner, do they talk to the planning department? Artists see how these things connect.

There were moderators of these visioning sessions that were legally trained. Everything we said had to be translated into these bulleted, slightly legalese points for them to be digested as policy. At the time, I was sort of amazed that they could translate, although it felt like the spirit of it was lost. Later it struck me that you couldn’t just take what we were saying and have someone in power really hear it. And we were invited to the table: we were not “protestors.” And yes, maybe these were radical ideas. But you invited us to deliver them. Most of which I haven’t seen actually implemented, even in their translation.

I think about all of these things that aren’t stitched together in Chicago. The work Paola Aguirre is doing with the Overton school in rethinking how a school infrastructure can function as a community space. Or the ongoing project that I participated in at the National Public Housing Museum. Or Emmanual Pratt at Sweet Water Foundation. Or the work that you and many of your colleagues are doing in the Parks. The note-takers in power who need to pay attention to stitch these things together aren’t stitching things together. So these experiments don’t have the power they could have. I didn’t have the answers to change this dynamic. But I’m left with questions about how one interjects in those larger institutional contexts.

Irina: What I’m hearing you say is that you’ve been in the room where it happens.

Todd: Yeah, the resistance to change is actually happening in the room.

Irina: I really feel that because right now, there’s police brutality and protest but there’s also this structural violence, which is defunding... and whether it’s the schools or the parks or social services, this pandemic and this economic recession is not going away. And what you’re talking about… not having the people who are there stitching, who are showing these narratives, who are showing the value of this work, it feels like either these grassroots solutions can be amplified and can take over for these failed institutions or they’re just wiped out because they can’t survive this moment.

I feel a lot of hope because of all the crowdsourcing that’s happening and all the bottom-up support that people are doing and not waiting for a funder or institution. There’s also a lot of accountability that’s happening and is being demanded. When your mandate is to ultimately make money for the city, what is the space for resistance fit in there? And it’s scary, like the things happening in Portland… protestors being kidnapped and taken to black sites and tortured, it’s next level. Perhaps, I’m only saying that because now it’s white people being tortured and disappeared and the media is finally reporting on it.

Todd: That’s where we are...and I’m typically the hopeful person. I think it’s possible in thinking of this time being folded. And we have these dark moments. The dark moments collectively are not separate from our personal darkness. Our personal pain and our collective pain are so often linked. Or the dark thinking, hopeless thinking we grew up with or that’s socially derived. But we’re not getting outside and seeing the whole.

I do find this is why I prepare because a lot of my life has been writing and note-taking, which can be its own kind of madness but often it’s an anchor, like “Oh, I wrote this down!” and it reminds me of what was once clear for a fleeting moment. I’ll go through a journal and it’ll remind me that I’ve felt a certain way before and it also reminds me that I survived it.

We have to give us this self-care so we can give to others and then scaffold change out together. I’ve been thinking about myself, the self, in this society that’s so very individualistic. And thinking about how to recuperate the self and value it against the insane kind of individualism that we see with people who don’t wear masks. And musing on how to have a self immersed in collective projects, collective care and collective benefit and communal ways of doing things. For someone who’s used to, maybe for the wrong reasons, taking myself out of the picture -- I’m wondering how to balance being in the picture as an individual. Without going into that place of egotism and individualism. For me, that’s critical of getting to the place of answering the question, “What do I do next?”

In those rooms, there is a lot of resistance to ideas like, “Let’s decolonize the Cultural Center” -- there were some very strong reactions from people in cultural policy making of Chicago. If I psychoanalyze it, I can talk about systemic racism and colonial mindset, but on a personal level,

“the people that are most egotistical are the most fragile and unrealized as people and they’re projecting the potential loss of their power, which is fragile to begin with.”

We don’t make the space to work on ourselves in the same way we make the space to indulge in ourselves.

Yeah, you’re indulging your fantasies, your militaristic whatever, it’s not dealing with the wounds and vulnerabilities however they manifest and focusing on taking care of them.

Irina: I love that distinction.

Todd: Going back to this kind of work, the pressure of delivering half a million tourists in this system of time where there is no time... we’re just producing. Maybe we’re producing an intervention that does decolonize the Cultural Center -- it sounds like you could just do it and it’s done -- but intervene very strongly to bring a decolonized perspective to that place and we draw light on the work folks are doing, but then the cultural machine just has to keep going. It doesn’t stop and reflect or slow down and digest. So for our Cultural Affairs, which is also Special Events, which the department is already designed to be a machine to deliver tourists and supposed economic benefits. It’s like, tomorrow is the Taste of Chicago and next week is something else, something is always churning… and there will always be another Architecture Biennial somewhere in the world. It’s not like, “Let’s take this artist apparatus and apply it to real problems in the city.”

This is what I spend my time doing...diving into my archives and then looking up at how I connect to what’s going on. Trying to reconcile with the way systems operate and manage themselves because at the end of the day systems are people running it and if you are that person, who are you and what are you doing?

I like the word “ecosystem” and people overuse it. But what if there were real cultural ecosystems that were like the actual natural ecosystem of the planet? If our human-designed governments and our human-made siloed projects ... that become a school department or a sanitation department...what If all these human-made things that support our living together communally, become like natural systems? For me, fundamentally decolonizing the Cultural Center isn’t the signs calling out exploitation at an exhibition. But drawing our lasting attention to the ways we’ve been separated from the planet.

Architecture is the kind of container and symbol of the kind of system that was created, which we can call colonial or racist. The resistance to taking down this monument is emblematic of what ails us. I can see how, for some people, it could be hard to grasp abolition. But you would think it would be easy to grasp this monument that was created at a time when Mussolini was advocating for it. Like we should all be able to wash our hands of that pretty easily. The fact that we can’t is pretty damning.

Irina: It’s the worst police brutality that I’ve ever seen in Chicago and obviously individual Black people have been killed and masses have been killed, but at a protest, it wasn’t this bad over Mike Brown… it was all over a fucking statue.

Todd: The thing to me that’s striking is that it didn’t have to become a protest. That could’ve been a position to take it down.

Irina: I think it goes back to what you were saying about fragile egos and the people who have done the least self-work have the most fear and feeling like they have the most to lose and that’s where the state is right now.

Todd: Columbus is like Santa Claus: such a myth to begin with. I’ve known as a child that it was a myth. How did we become so attached to defending something that’s mythical? The Italian community, which is not monolithic, were not wholly considered white prior to this narrative. This happened in our lifetimes and it needs to be demystified. The way that it’s been talked about is that keeping the sculpture is the education. No, taking it down is the education. The discourse about this work of art as “property” is very telling. And informs the more difficult conversation that we’re having around police abolition. Because it actually makes the point: what are the police protecting? In fact, it is these systems of racism, of private property, of extraction, of causation… so the education has happened. But it didn’t have to happen with people beaten and assaulted and harmed.

Irina: It’s also shocking how that hasn’t been universally acknowledged. So many news outlets, “Oh these organizers tried to take down the statues and the cops stopped them.” And that’s it. The police brutality isn’t even being made visible in mainstream media.

Todd: I had to go look, thinking it can’t be that one day, the day that I learned there will be a protest that people said, “Let’s go pull the statue down.” In fact, no, there’s been petitions and demands for at least a month, maybe more, that led to this. That’s also left out of the mainstream coverage. It appears to be this spontaneous, irrational thing… but actually, the city had every opportunity to take the steps they probably will have to take… They’re “Studying” the monuments…

Irina: What the fuck do you need to study?!?

Todd: New York did such a study some time ago recently and handled it very poorly.

Irina: Meanwhile, there are 3rd and 4th graders protesting DouglasS Park, but there is a law that where parks’ names can’t be changed if they’re named after a person…

Todd: These rules make no sense… who’s the constituency of that role? Like, who cares? It’s Chicago.

Irina: Right, like is Steven Douglas’ family here? In a majority Black community, you’re going to stake your claim on a slave owner's name to a park? That’s the side of history you want to be on? What level of accountability is necessary to shift these institutions because they don’t listen to children, they don’t listen to organizers, they don’t listen to community members signing petitions. Does it take tanks and people being beaten and arrested? What does it take? Does someone need to just come in the night and topple things? Within capitalism, does it have to hurt their bottom line so that they look so bad that they have to change it?

I mean in the words of James Baldwin, “I don’t have time for your reform.” Miracle Boyd, an 18 year old organizer from Good Kids Mad City got her teeth knocked, people are being snatched off the street, this is not okay. I don’t want to sit around and wait for the next city council meeting.

Todd: Let’s say we win the battle of abolition. Then we are defining the new system, as the ecosystem. There has to be some way of re-organizing the massive, incomprehensible bureaucracy that existed because we don’t want that. But somehow resources are being collected. And they’re sitting in the pot called police. And now those resources go somewhere else… how do we make an accountable, collective, communal way of assigning those resources to the things that we need? That’s where the revolution or radical change has to perpetuate itself as a form of governance. I think we have something to learn from Native people in that regard because they have other ways of governing and co-existing and resource-allocation and sharing.

Irina: Absolutely.

Todd: It’s hard to see what the trigger point of radicalizing will be. But on the other side of radical change, there’s so many possibilities of what that world looks like that we all want to live in. How can we make it a world that works?

Irina: Nature isn’t capitalist, you know? Darwin was wrong, it’s not about survival of the fittest. It’s about interdependence… what you’re saying about learning from Indigenous practices, learning from nature, that’s absolutely what we have to do because otherwise we’re just perpetuating these harmful, oppressive dynamics. We can’t just defund the police and then keep everything else exactly as it is and hope it’ll all work out.

Todd: You’re helping me gain my clarity as well because there isn’t a magic wand from the days past to a more egalitarian, equitable, non-racist future. It will be messy to get from one to the next. But we need the examples of what that looks like on the other side. Not just images of what that looks like. But operational models of that new living together. We need to keep at it because those are also the spaces that shelter us and protect us in the messiness.

It won’t be just one day like, “Oh, racism’s solved!” “If we live in this carceral state and everything is about punishment and you are the victor and someone else is going to take power, the only universe you can imagine is one where those who were in power are being punished in your system, which could be a satisfying sci-fi movie, but we’re talking about the world we want to live in then that’s actually not what happens.” But those people can’t see it, they can’t imagine a world where they’re not being sent to a gulag.

These cultural programs, right now, are not seen as core or essential. They’re considered nice to have and then we go back to business as usual. Since there won’t be a magic wand in protecting these experiments, which should be modeling the world that we all live in, until then they are islands of shelter in the world that we actually live in.

Irina: It’s the spaces and the practices. How are we practicing abolition in our everyday lives? How are we addressing harm? How are we addressing accountability without punishment?

“It’s not enough to defund the police if we’ve all internalized policing.”

I’m also grappling with these ideas and hearing you talk about it reminds me, yes this is what we’re doing and this is what we’re building towards and we have to build the practices and the community while at the same time toppling the monuments, the institutions, and the state.

Todd: A critique that I’ve heard -- which comes from our societal models -- on my style of leadership is that it’s too facilitative. People like to think that the leader is a punisher -- they want that!

Irina: I’ve gotten that too! I’ve gotten, “You’re too nice….” and “You need to give them the iron fist every once in a while.” Really? That’s what you want?

Todd: I’m not here to be the expert. I’m here to help you all (all of us) figure it out. That being said, I learned something from this really amazing team of curators I worked with, including that I’m conflict-averse. With their prompting, I had to lean into conflict many more times than would be my preference. I had to show up and stand my ground in ways that were exhausting. But that’s part of leadership. One can be facilitative and also be firm and not afraid of conflict. How do we balance that?

Irina: I really appreciate problem-solving with you because it is easy to feel alone and to go out in the forest and scream and feel like no one can hear you. That was definitely me last night… I feel like a lot of youth work, educational work, partially because it’s feminized, is undervalued. It’s always the first thing to get cut. But you’re reminding me that these are the spaces where we practice abolition. These are the spaces where we learn how to hold ourselves and each other accountable. Starting that from an early age is so powerful and important. So I just want to thank you for reminding me. This is why we’re doing what we’re doing and we need to demand for it to get the respect it deserves.

So my closing question is the Grace Lee Boggs’ question: What time do you think it is on the clock of the world?

Todd: We’ve talked a lot about time and its circularity and its foldedness. For me it’s that time before dawn, which can be the hardest time. Time is warped when you have anticipation… and then, time can seep through your fingers but if you’re waiting for something. The same three minutes can look very different. This also happens when we’re in pain. Time slows and seems interminable. Recognizing that perhaps there’s this moment of dawn, this moment of possibility.

I’ve also been thinking about the Poor People’s Campaign a lot -- it was a historical movement I became aware of in the context of the Civil Rights Museum in Memphis years and years ago. I’ve been thinking about how they manifested resistance as city-building. The Poor People’s Campaign went to march in Washington but also built Resurrection City, which was a kind of pop-up city on the mall. As I think about art activations as islands of possibility I turn to images of Resurrection City grown out of protest... I imagine when that statue is torn down, a space that could be claimed, the parks department collaborating with artists to redefine a collective space for learning.

They named their city for resurrection in 1968, the year I was born, at a time that must have seemed equally bleak. One could argue the intervening 52 years between now and then -- I lived it -- was it better or worse? That resurrection city doesn’t exist, but many of the principles it manifested was about the city as care, accountability, ways of communing together, collective purpose, living together. So it feels like we’ve awakened to night terror, and that dawning vision is yet to come, but maybe it’s closer than we think. How do we create space where we persist, survive and have hope for the coming light when it feels very dark? That’s what time I think it is.

____

This conversation was lovingly transcribed and edited by my dear friend, writer, and cultural organizer Rivka Yeker. You can check out their work at @hooliganmagazine.